Congenitally Corrected Transposition

Download this information sheet as a PDF

The aim of this information sheet is to explain what Congenitally Corrected Transposition (aka discordant transposition or inversion) is, what effect it will have on a child and how it can be treated.

Animation of Corrected Transposition

Animation of normal heart

facWhat is Congenitally Corrected Transposition?

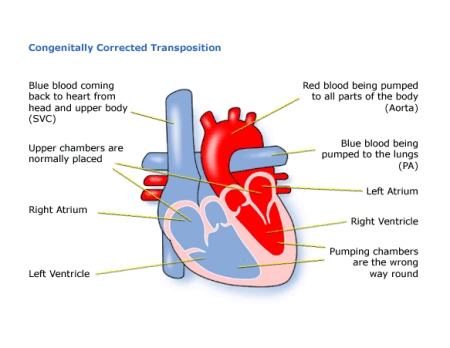

It is a rare congenital heart disorder where the pulmonary artery and the aorta are the wrong way around (Transposition of the Great Arteries), but this has been ‘corrected’ by the fact that the ventricles are also switched around.

This means that the right atrium is connected to the left ventricle and this is connected to the pulmonary artery. On the left hand side, the left atrium is connected to the right ventricle and this is connected to the aorta. The right ventricle therefore pumps the blood to the body and the left ventricle pumps the blood to the lungs. In the normal heart, it is the other way round. However, because the arteries are also switched around, blue blood is still pumped into the lungs and red blood is pumped into the body.

Like many other heart conditions this one varies enormously from child to child. There are usually other defects as well – the most common are:

- Ventral septal defect (VSD) below the pulmonary artery

- Pulmonary stenosis

- Ebstein’s anomaly

- Complete heart block

- Abnormal and leaking valves

Diagnosis

Congenitally Corrected Transposition may have been diagnosed during pregnancy, although it may have been thought to be simple transposition (TGA).

After birth your baby appears to be normal as blood is flowing the right way round. However, if there are any other associated defects present such as pulmonary stenosis, then your child may have a heart murmur. The sound of extra blood being pushed towards the lungs and leaking through the valve can be heard as a heart murmur.

When a heart murmur is heard the tests used can be:

- pulse, blood pressure, temperature, and number of breaths a baby takes a minute

- listening with a stethoscope for changes in the heart sounds

- an oxygen saturation monitor to see how much oxygen is getting into the blood

- a chest x-ray to see the size and position of the heart

- an ECG (electrocardiogram) to check the electrical activity

- an ultrasound scan (echocardiogram) to see how the blood moves through the heart

- checks for chemical balance in blood and urine

- a catheter or Magnetic Resonance Imaging test may be needed

If your child has congenitally corrected transposition with no other defects, they may not have any symptoms and may not need any treatment. If your child has other defects, however, they may develop symptoms because of these and will probably need treatment.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to support the heart and protect the lungs from high blood flow if there is a VSD present. This could mean open heart surgery:

- to close the VSD;

- to repair or replace valves;

- to remove any narrowing below the pulmonary artery; or

- more complicated surgery to redirect the flow of blood into the correct chambers.

If your child has other heart defects, the kind of surgery needed will depend on how the heart can best be modified to cope with all the problems he or she has.

If your child has complete heart block, a pacemaker can be implanted at a very young age. For most children this surgery is low risk, but it can depend on how well your child is otherwise. The doctors will discuss risks with you in detail before asking you to consent to the operation.

For open heart surgery the length of time in hospital will usually be only 10 to 12 days, of which one or two is normally spent in the intensive care and high dependency unit. Of course this depends on how well your child is before and after the surgery, and whether any complications arise.

How it affects your child

If the open heart surgery is straight-forward, and your child does not have other health problems, he or she should be completely well shortly after surgery. Most parents are amazed at how quickly their child recovers from surgery and starts to gain weight.

There will be a scar down the middle of the chest, and there may be small scars where drain tubes were used. These fade very rapidly in most children, but they will not go altogether. Smaller scars on the hands and neck usually fade away to nothing.

It is common for the valves to leak a little as your child grows older, but if this becomes severe, they sometimes need further repair or even replacement with an artificial valve. If the valve is replaced, this will need to be monitored to make sure the replacement is working effectively, and an artificial valve may need to be replaced as the child grows.

Children with artificial valves will also need to take anticoagulants for the rest of their lives, which can have a number of implications for their health and lifestyle (see the Warfarin Information sheet).

Evidence and sources of information for this CHF information sheet can be obtained at:

(1) National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. NICE Guidance IPG505.

Telemetric adjustable pulmonary artery banding for pulmonary hypertension in infants with congenital heart defects. London: NICE; 2017. Available at:

www.nice.org.uk/guidance/IPG505

(2) National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Structural heart defects overview. London: NICE; 2017. Available at:

https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/structural-heart-defects

(3) NHS Choices. Congenital heart disease treatment. London: NHS; 2017. Available at:

www.nhs.uk/conditions/congenital-heart-disease/pages/treatment.aspx

(4) NHS Choices. Warfarin. London: NHS; 2017. Available at:

https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/warfarin/

About this document:

Published: June 2013

Reviewed: May 2022

To inform CHF of a comment or suggestion, please contact us via info@chfed.org.uk or Tel: 0300 561 0065.